Hi! This is my very first blog entry! I’ve created this blog to do both force myself to publish more of my study notes as well as to share as much as I can online so I hope you enjoy it. =)

Disclaimer

- It’s important to mention this research is a work in progress and might receive updates in the future. If you find anything wrong here please let me know and I’ll be happy to fix it!

- The code snippets presented in this blogpost were obtained from the Golang source code. To make it easier to understand I added some more comments on it and removed some parts of the code for better visualization.

- When I started this research I found no one talking about these internals aspects, specially how those could be abused so I’m assuming what I’m presenting here is a kind of “novel approach” (uuuh, fancy… hahaha). If you know someone that did this kind of work in the past please let me know! I would love to check it.

Motivation

At the end of last year (2022) I had to analyze some obfuscated and trojanized Go malwares, basically perform some triage to know more about what it does and how it does the stuff. Due to the Go nuances and runtime aspects my first approach was analyze it statically and after some time into it I thought I was wasting too much time for what should be just a simple triage in the first place.

That said, I decided to go to a dynamic approach and my first idea was something that I think most part of RE people would do: trace the API calls. In order to do that I used API Monitor cause it’s easy to use and very powerful. Unfortunatelly the output was very noisy and not that complete and I was not happy with it. This experiment made me ask myself why it’s that noisy? How are those Windows API calls performed? And this is how I started this research.

From a Golang function to the Windows API

The big question we want to answer in this blogpost is: what happens when an application compiled using Go calls a function? Regardless what it does in the middle the program would need to either compile the Windows libraries statically or call into the OS functions at some point (e.g. calling the exported function, performing the syscall directly, etc)

A simple Go call

To answer that question, let’s take the Hostname function from the os package as an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

package os

// Hostname returns the host name reported by the kernel.

func Hostname() (name string, err error) {

return hostname()

}

As we can see, this function is just a wrapper for another function named hostname, also defined in the os package:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

func hostname() (name string, err error) {

// Use PhysicalDnsHostname to uniquely identify host in a cluster

const format = windows.ComputerNamePhysicalDnsHostname

n := uint32(64)

for {

b := make([]uint16, n)

err := windows.GetComputerNameEx(format, &b[0], &n) // Our target

if err == nil {

return syscall.UTF16ToString(b[:n]), nil

}

if err != syscall.ERROR_MORE_DATA {

return "", NewSyscallError("ComputerNameEx", err)

}

// If we received an ERROR_MORE_DATA, but n doesn't get larger,

// something has gone wrong and we may be in an infinite loop

if n <= uint32(len(b)) {

return "", NewSyscallError("ComputerNameEx", err)

}

}

}

Despite some checks performed this function is very simple, it just calls a function named GetComputerNameEx in the windows package in order to get the hostname. The curious thing about it is that the name of this function is also the name of a Windows API function that is also used to retrieve the hostname.

Doing a quick search in the Go source code we can find the function implementation and notice it ends up calling a function named Syscall:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func GetComputerNameEx(nametype uint32, buf *uint16, n *uint32) (err error) {

r1, _, e1 := syscall.Syscall(procGetComputerNameExW.Addr(), 3, uintptr(nametype), uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(buf)), uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(n)))

if r1 == 0 {

err = errnoErr(e1)

}

return

}

To understand what’s going on here let’s start looking at the procGetComputerNameExW variable being passed as the first parameter to the Syscall function.

Checking a bit more into the windows package source we can see this procGetComputerNameExW variable being initialized earlier using both the NewLazyDLL and NewProc functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

moddwmapi = NewLazySystemDLL("dwmapi.dll")

modiphlpapi = NewLazySystemDLL("iphlpapi.dll")

modkernel32 = NewLazySystemDLL("kernel32.dll") // Our target module

modmswsock = NewLazySystemDLL("mswsock.dll")

modnetapi32 = NewLazySystemDLL("netapi32.dll")

// reducted

procGetCommTimeouts = modkernel32.NewProc("GetCommTimeouts")

procGetCommandLineW = modkernel32.NewProc("GetCommandLineW")

procGetComputerNameExW = modkernel32.NewProc("GetComputerNameExW") // Our target function

procGetComputerNameW = modkernel32.NewProc("GetComputerNameW")

procGetConsoleMode = modkernel32.NewProc("GetConsoleMode")

The first thing to notice here is that there’s a lot of real Windows API function and DLL names being passed to those functions. At this point we can start to assume this might have something to do with the API itself, so let’s keep going!

What those two functions being used do is simply initialize the procGetComputerNameExW variable as a LazyProc and that will basically allow it to have access to the Addr function, which is the function being called in the parameter for the syscall.Syscall call:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

// NewLazyDLL creates new LazyDLL associated with DLL file.

func NewLazyDLL(name string) *LazyDLL {

return &LazyDLL{Name: name}

}

type LazyDLL struct {

Name string

// System determines whether the DLL must be loaded from the

// Windows System directory, bypassing the normal DLL search

// path.

System bool

mu sync.Mutex

dll *DLL // non nil once DLL is loaded

}

// NewProc returns a LazyProc for accessing the named procedure in the DLL d.

func (d *LazyDLL) NewProc(name string) *LazyProc {

return &LazyProc{l: d, Name: name}

}

// A LazyProc implements access to a procedure inside a LazyDLL.

// It delays the lookup until the Addr function is called.

type LazyProc struct {

Name string

mu sync.Mutex

l *LazyDLL

proc *Proc

}

Resolving the Windows API functions

Once the Addr function is called it performs some calls here and there but the important function it calls is named Find. This function calls a function named Load followed by one named FindProc:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

// Addr returns the address of the procedure represented by p.

// The return value can be passed to Syscall to run the procedure.

// It will panic if the procedure cannot be found.

func (p *LazyProc) Addr() uintptr {

p.mustFind()

return p.proc.Addr()

}

// mustFind is like Find but panics if search fails.

func (p *LazyProc) mustFind() {

e := p.Find()

if e != nil {

panic(e)

}

}

func (p *LazyProc) Find() error {

// Non-racy version of:

// if p.proc == nil {

if atomic.LoadPointer((*unsafe.Pointer)(unsafe.Pointer(&p.proc))) == nil { // Check if the func addr is not resolved already

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

if p.proc == nil {

e := p.l.Load() // Attempt to load the module

if e != nil {

return e

}

proc, e := p.l.dll.FindProc(p.Name) // Resolve export function addr

if e != nil {

return e

}

// Non-racy version of:

// p.proc = proc

atomic.StorePointer((*unsafe.Pointer)(unsafe.Pointer(&p.proc)), unsafe.Pointer(proc))

}

}

return nil

}

If you’re a bit familiar with Windows and RE you probably already figured what’s going on here. The Load function is responsible for loading the module in which exports the requested Windows API function and FindProc resolves the exported function address. This steps are performed using the classic combination of LoadLibrary + GetProcAddress:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

func (d *LazyDLL) Load() error {

// Non-racy version of:

// if d.dll != nil {

if atomic.LoadPointer((*unsafe.Pointer)(unsafe.Pointer(&d.dll))) != nil { // Check if the module is loaded already

return nil

}

d.mu.Lock()

defer d.mu.Unlock()

if d.dll != nil {

return nil

}

// kernel32.dll is special, since it's where LoadLibraryEx comes from.

// The kernel already special-cases its name, so it's always

// loaded from system32.

var dll *DLL

var err error

if d.Name == "kernel32.dll" {

dll, err = LoadDLL(d.Name) // Wrapper to syscall_loadlibrary

} else {

dll, err = loadLibraryEx(d.Name, d.System) // Wrapper to LoadLibraryExW

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Non-racy version of:

// d.dll = dll

atomic.StorePointer((*unsafe.Pointer)(unsafe.Pointer(&d.dll)), unsafe.Pointer(dll))

return nil

}

func LoadDLL(name string) (dll *DLL, err error) {

namep, err := UTF16PtrFromString(name)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

h, e := syscall_loadlibrary(namep) // Perform the LoadLibraryA call

if e != 0 {

return nil, &DLLError{

Err: e,

ObjName: name,

Msg: "Failed to load " + name + ": " + e.Error(),

}

}

d := &DLL{

Name: name,

Handle: h,

}

return d, nil

}

// loadLibraryEx wraps the Windows LoadLibraryEx function.

//

// See https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/ms684179(v=vs.85).aspx

//

// If name is not an absolute path, LoadLibraryEx searches for the DLL

// in a variety of automatic locations unless constrained by flags.

// See: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ff919712%28VS.85%29.aspx

func loadLibraryEx(name string, system bool) (*DLL, error) {

loadDLL := name

var flags uintptr

if system {

if canDoSearchSystem32() {

flags = LOAD_LIBRARY_SEARCH_SYSTEM32

} else if isBaseName(name) {

// WindowsXP or unpatched Windows machine

// trying to load "foo.dll" out of the system

// folder, but LoadLibraryEx doesn't support

// that yet on their system, so emulate it.

systemdir, err := GetSystemDirectory()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

loadDLL = systemdir + "\\" + name

}

}

h, err := LoadLibraryEx(loadDLL, 0, flags) // Wrapper to syscall.Syscall using procLoadLibraryExW

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &DLL{Name: name, Handle: h}, nil

}

// FindProc searches DLL d for procedure named name and returns *Proc

// if found. It returns an error if search fails.

func (d *DLL) FindProc(name string) (proc *Proc, err error) {

namep, err := BytePtrFromString(name)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

a, e := syscall_getprocaddress(d.Handle, namep) // Perform the GetProcAddress call

if e != 0 {

return nil, &DLLError{

Err: e,

ObjName: name,

Msg: "Failed to find " + name + " procedure in " + d.Name + ": " + e.Error(),

}

}

p := &Proc{

Dll: d,

Name: name,

addr: a,

}

return p, nil

}

What version of the LoadLibrary function it uses? It depends. During the runtime initialization it uses LoadLibraryA to load kernel32.dll and LoadLibraryExA to load the rest of the modules the runtime requires. All the other modules are loaded via LoadLibraryExW. Of course this can change in future versions of Go so what really matters here is that the module will be loaded.

Once the address of the desired function is obtained it’s returned by the previously mentioned Addr function and passed to the syscall.Syscall function.

Very nice, right?! This is exactly how Golang resolves the address of (almost) all the Windows API functions required by a Golang application. So yes, it’s basically the classic runtime linking approach.

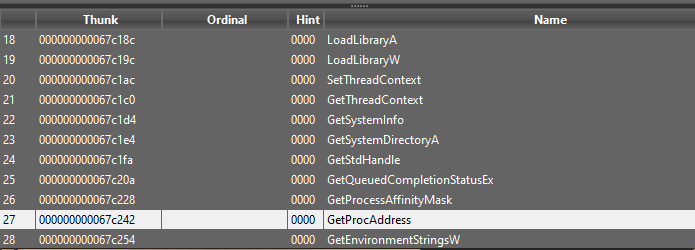

Now you might be wondering: ok, the desired Windows API functions are resolved using GetProcAddress, but how is the address of GetProcAddress function resolved? Well, there’s no magic here. The GetProcAddress address, along with other functions the runtime package depends on are present in every Golang application Import Table, so their addresses are resolved by the Windows Loader in load time.

Example of the Import Table of a Golang application using DIE

Example of the Import Table of a Golang application using DIE

Another question that you might ask is: are literally all the Windows API functions resolved this way? Well, not exactly. As mentioned already, some functions used by the runtime package would be resolved by the Windows loader, but there’s some others that seems to be “optional” (but still part of the runtime package and still resolved) that would take a different path and do not rely on those “Syscall” calls. Those would use calls with the stdcall prefix. However, regardless the path it takes those would still rely on GetProcAddress and will take the same “final path”. We’ll learn more about it in a bit.

Since most part of the functions we care about (the ones that are not part of the runtime) are resolved using the Syscall path we’ll focus on those.

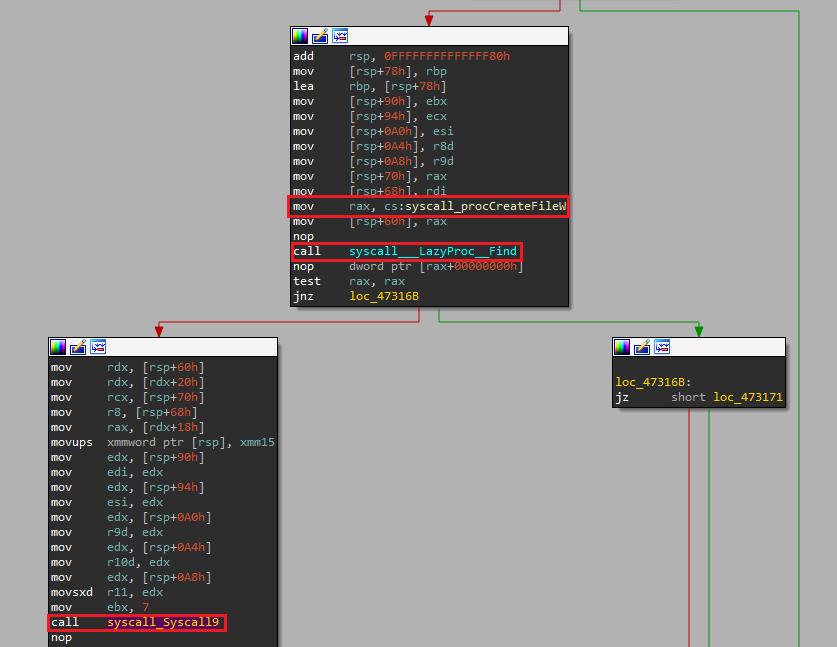

That said, if we search for some function named like “syscall_whatever” (e.g. syscall_CreateFile) in a tool like IDA we’ll always see exactly the functions we discussed being called (i.e. Addr followed by a Syscall<n>).

Disassembly view of syscall_CreateFile in IDA

Disassembly view of syscall_CreateFile in IDA

If you want to play with what we’ve learned so far here’s a nice exercise for you: a way to monitor what Windows API functions are being resolved by a Go application is setting a conditional breakpoint at GetProcAddress using x64dbg and logging the second parameter to the call (lpProcName). Then you can use something like {utf8@rdx} (x64 environment in this case) as the log text and 0 as the break condition to make sure it will not break. By doing so you’re going to see functions from all the packages being resolved in the Log output:

Example of the functions resolved by a Go application using x64dbg

Example of the functions resolved by a Go application using x64dbg

Since both the runtime package and the other dependencies would rely on GetProcAddress the output would be a bit noisy, but still interesting. By the end of this article we’ll learn how to filter the noise and only get the functions being resolved by the main package.

Now that we kind of understand part of the chain the remanining question is: how are the calls actually performed? How the Go package interacts with the Windows API? We saw functions like syscall_getprocaddress being called or even the syscall.Syscall one, but what exactly happens there?

Before we move forward I would like to give a step back and introduce a few more concepts to make the rest of the reading easier to follow.

Goroutines

A goroutine can be defined as a function executing concurrently with other goroutines in the same address space. Go implements an architecture that uses way less resources than the regular threads to execute code. Some examples that make goroutines kind of better in terms of performance when compared against the regular multithreading model is that usually it’s stack start very small (around 2KB) and it doesn’t need to switch to kernel mode or save too much registers in the context switch.

All the goroutines are handled by an usermode scheduler implemented in the Go runtime package. During execution the Go runtime creates a few threads and schedules the goroutines onto those OS threads to be executed. Once a goroutine is blocked in an operation (e.g. sleep, network input, channel operations) the scheduler changes the context to other goroutines, with no impact in the real threads. This architecture makes Go applications very performatic cause although they’re multithread some of the negative impacts caused by the classic multithread approach are handled by the runtime.

Of course regardless this abstraction the code would still end up going through the real thread, but the key here is the design of the language.

The Go Scheduler

Go implements a scheduler that works in an M:N model, where M goroutines are scheduled onto N OS threads throughout the program execution. The scheduler manages three types of resources:

G: represents a goroutine and contains information about the code to execute.M: represents an OS thread and where to execute the goroutine code.P: represents a “processor”. Basically a resource that is required to execute Go code. The max number of Ps is defined in the GOMAXPROCS var.

Each M must be associated to a P and a P can have multiple M, but only one can be executing. The scheduler works with a global and a local queue of goroutines and manages their execution using a work sharing/stealing model.

And how Go creates/handles these structures for each thread? It uses the Windows Thread Local Storage (TLS) mechanism.

The Go system calls

Alright, now let’s go back to the GetComputerNameEx function. Remember the syscall.Syscall call? It turns out that Golang defines several functions using the “Syscall” prefix and those are all wrappers to another function named SyscallN:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

//go:linkname syscall_Syscall syscall.Syscall

//go:nosplit

func syscall_Syscall(fn, nargs, a1, a2, a3 uintptr) (r1, r2, err uintptr) {

return syscall_SyscallN(fn, a1, a2, a3)

}

//go:linkname syscall_Syscall6 syscall.Syscall6

//go:nosplit

func syscall_Syscall6(fn, nargs, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6 uintptr) (r1, r2, err uintptr) {

return syscall_SyscallN(fn, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6)

}

//go:linkname syscall_Syscall9 syscall.Syscall9

//go:nosplit

func syscall_Syscall9(fn, nargs, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7, a8, a9 uintptr) (r1, r2, err uintptr) {

return syscall_SyscallN(fn, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7, a8, a9)

}

//go:linkname syscall_Syscall12 syscall.Syscall12

//go:nosplit

func syscall_Syscall12(fn, nargs, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7, a8, a9, a10, a11, a12 uintptr) (r1, r2, err uintptr) {

return syscall_SyscallN(fn, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, a7, a8, a9, a10, a11, a12)

}

// etc

The rule for the number following the “Syscall” prefix is based on the number of arguments the function takes. The Syscall takes up to 3 arguments, the Syscall6 takes from 4 to 6, the Syscall9 takes from 7 to 9 and so on.

Why Go implements it this way? I’m not sure, maybe to avoid the need to create a “Syscall” function for each number of arguments (e.g. Syscall1, Syscall2, Syscall3, etc), making it more generic?! I don’t know. The “downside” of this approach is that the number of parameters provided by Go to an API function might not be precise (e.g. CreateFileW would be invoked using 9 parameters but the real API call takes only 7). Either way, that would still work cause Windows would not care about it and only handle the real parameters.

Anyway, let’s see how SyscallN is implemented in the runtime package:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

func syscall_SyscallN(trap uintptr, args ...uintptr) (r1, r2, err uintptr) {

nargs := len(args)

// asmstdcall expects it can access the first 4 arguments

// to load them into registers.

var tmp [4]uintptr

switch {

case nargs < 4:

copy(tmp[:], args)

args = tmp[:]

case nargs > maxArgs: // Check if the number of args is more than the suported value

panic("runtime: SyscallN has too many arguments")

}

lockOSThread()

defer unlockOSThread()

// What we actually care about

c := &getg().m.syscall // Init the Golang system call structure

c.fn = trap // Set the Windows API function address

c.n = uintptr(nargs) // Set the number of arguments

c.args = uintptr(noescape(unsafe.Pointer(&args[0]))) // Set the arguments array

cgocall(asmstdcallAddr, unsafe.Pointer(c)) // Call the asmcgocall

return c.r1, c.r2, c.err

}

In this function we’ll focus on 2 things: the c variable initialization and the call to the cgocall function.

Regarding the initialization, remember the g we talked about in the scheduler introduction? The getg() function is the one responsible for getting the current goroutine information. In the snippet above it also access the m structure inside the g, which as we learned represents the thread the goroutine is associated to. It then access another structure named syscall and assign it to the c variable.

This syscall is of the type libcall and this structure defines all the information the Go runtime needs to perform a Windows API call:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// Defined inside the "m" struct in the "runtime" package

syscall libcall // stores syscall parameters on windows

// reducted

type libcall struct {

fn uintptr // Windows function address

n uintptr // Number of parameters

args uintptr // Parameters array

r1 uintptr // Return values

r2 uintptr // Floating point return value

err uintptr // Error number

}

Now that we know more about the libcall structure definition, the SyscallN operations start to be easier to understand. The initialization steps are the following:

c := &getg().m.syscall: initializecwith thelibcallstructure, allowing it to access the required Windows API information.c.fn = trap: set the resolved Windows API address (first parameter ofSyscallN).c.n = uintptr(nargs): set the number of arguments based on theSyscall<n>function used.c.args = uintptr(noescape(unsafe.Pointer(&args[0]))): set the array of arguments to be used in the API function (second parameter ofSyscallN)

Once it’s all set the c variable is then passed to the cgocall call as a parameter (a structure pointer), along with another variable named asmstdcall (a function pointer).

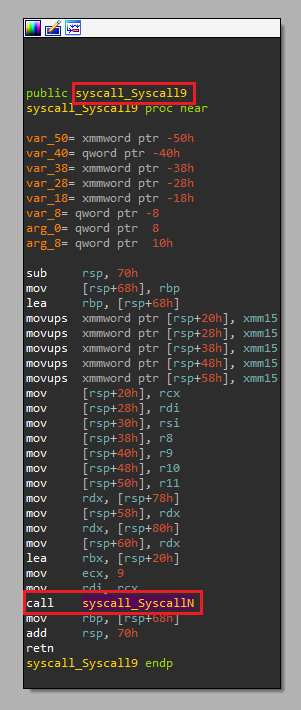

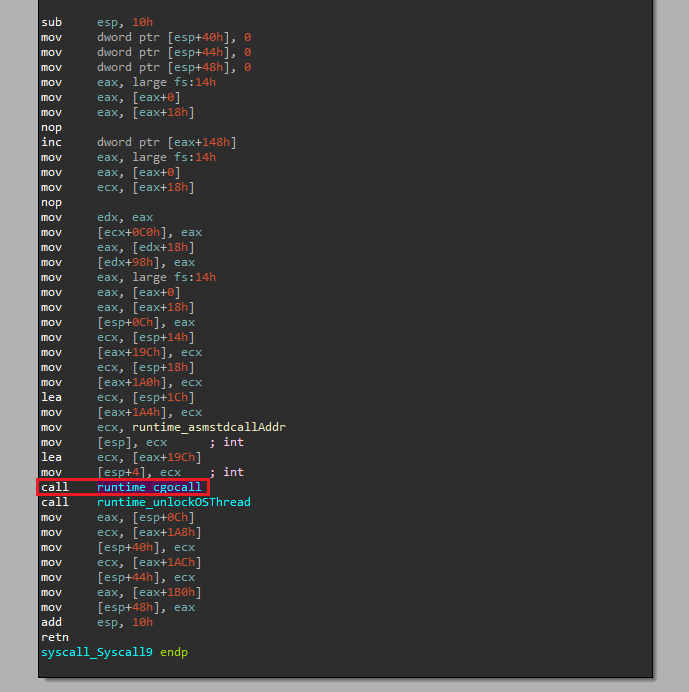

One thing that is important to mention is that for x86 binaries there’s no SyscallN so the cgocall is called by the Syscall<n> functions directly:

Example of a Syscall call in x64

Example of a Syscall call in x64

Example of a Syscall call in x86

Example of a Syscall call in x86

Now that we’ve learned a bit more about it all, remember the syscall_getprocaddress and syscall_loadlibrary calls? Since they are kind of special due to the fact they are resolved by the Windows loader they would not rely on the “Syscall” path, but as mentioned already the “final path” to actually perform the OS call is still the same. As we can see the steps it performs are pretty much the same of SyscallN:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

//go:linkname syscall_loadlibrary syscall.loadlibrary

//go:nosplit

//go:cgo_unsafe_args

func syscall_loadlibrary(filename *uint16) (handle, err uintptr) {

lockOSThread()

defer unlockOSThread()

c := &getg().m.syscall

c.fn = getLoadLibrary() // Get the address at the IAT

c.n = 1 // Hardcoded argc

c.args = uintptr(noescape(unsafe.Pointer(&filename)))

cgocall(asmstdcallAddr, unsafe.Pointer(c))

KeepAlive(filename)

handle = c.r1

if handle == 0 {

err = c.err

}

return

}

//go:linkname syscall_getprocaddress syscall.getprocaddress

//go:nosplit

//go:cgo_unsafe_args

func syscall_getprocaddress(handle uintptr, procname *byte) (outhandle, err uintptr) {

lockOSThread()

defer unlockOSThread()

c := &getg().m.syscall

c.fn = getGetProcAddress() // Get the address at the IAT

c.n = 2 // Hardcoded argc

c.args = uintptr(noescape(unsafe.Pointer(&handle)))

cgocall(asmstdcallAddr, unsafe.Pointer(c))

KeepAlive(procname)

outhandle = c.r1

if outhandle == 0 {

err = c.err

}

return

}

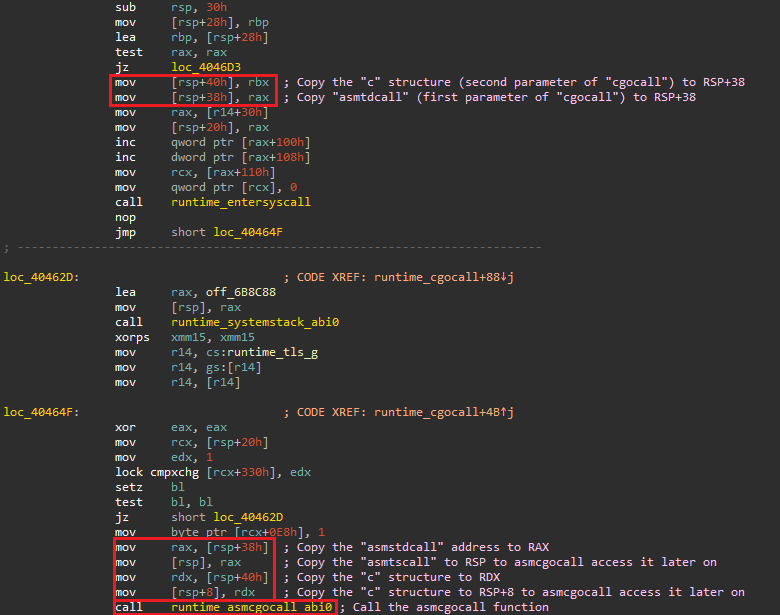

cgocall & asmcgocall

At this point we know that cgocall function receives both a variable named asmstdcall and a pointer to the c structure as parameters.

This function is responsible for things such as call the entersyscall function in order to not block neither other goroutines nor the garbage collector and then call exitsyscall that blocks until this m can run Go code without violating the GOMAXPROCS limit. Though this is not that important for our goal, the step that matters for us here is a call performed to a function named asmcgocall, passing the asmstdcall variable and the c structure to it (the fn and arg arguments passed to cgocall):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// runtime.cgocall(_cgo_Cfunc_f, frame)

func cgocall(fn, arg unsafe.Pointer) int32 {

// reducted

errno := asmcgocall(fn, arg) // func asmcgocall(fn, arg unsafe.Pointer) int32

Disassemlby view of the cgocall call

Disassemlby view of the cgocall call

Since we’re in a x64 environment due to the Go ABI the first parameter would be passed via RAX and the second via RBX.

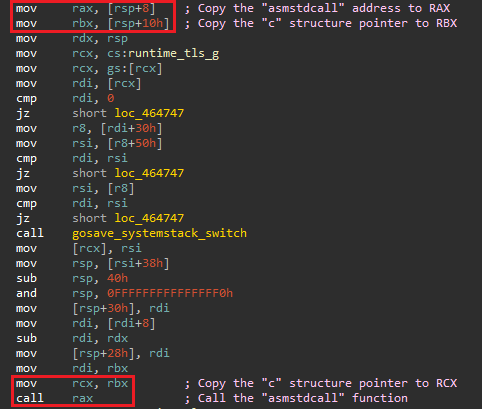

The asmcgocall function switches to a system-allocated stack and then calls the asmstdcall function (the variable passed to cgocall).

Both asmcgocall and asmstdcall functions are gcc-compiled functions written by cgo hence the attempt to switch to what Go calls the “system stack” to be safer to run gcc-compiled code.

Disassemlby view of the asmcgocall call

Disassemlby view of the asmcgocall call

asmstdcall: the “magic call gate”

We finally reached the most important function in this whole chain! The asmstdcall is the Go runtime function responsible for calling the real Windows API function. This function receives a single parameter passed through RCX in x64 and ESP+4 in x86. And what is received via this parameter? The famous c structure!

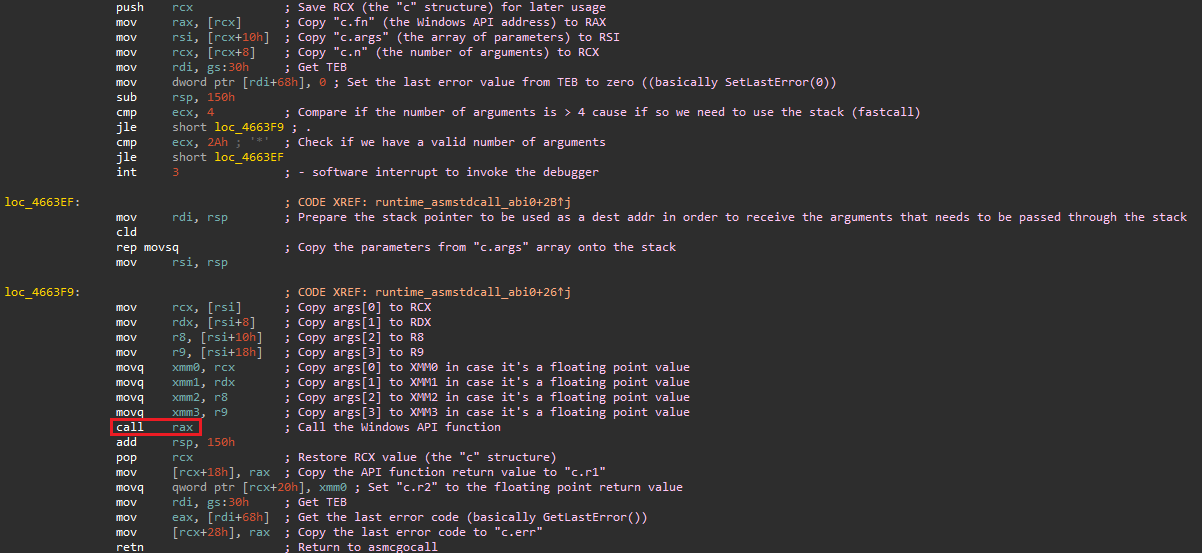

The image bellow is an example of the asmstdcall in a x64 environment. I added some comments in each assembly instruction to make it easier to understand:

Overall this function would simply prepare the registers for the API call (copy the parameters to the proper registers, use the stack if needed, etc), perform the call to the API itself and then set the results of it into the c structure.

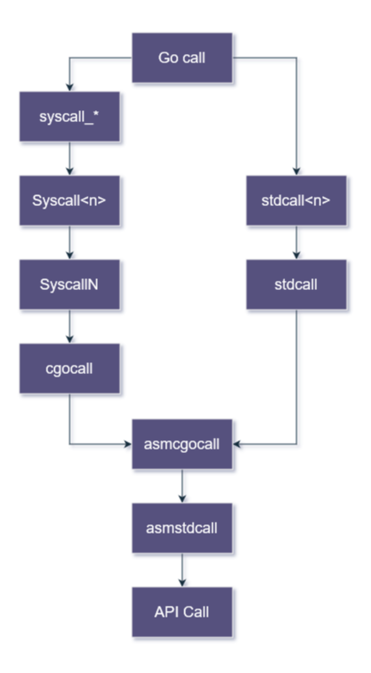

To summarize everything we’ve learned so far I’ve created a very simple image with the Go call flow:

General overview of how Go handles the API calls

General overview of how Go handles the API calls

This explanation finishes up the whole flow of how binaries written in Go would resolve and call the Windows API functions.

Tracing Golang Windows API calls with gftrace

As we can see, asmstdcall is a very powerful function, not only because it’s the one that performs the real Windows API call, but also because it manipulates all the relevant information needed for that call (e.g. function address, parameters, return value etc).

After a lot of tests I also noticed this function is present in a lot of Go versions (if not all), making this function very portable and reliable. I didn’t test all of the Go versions but I can say for sure it was there in a lot of different versions.

With that in mind, I decided to create a tool to “abuse” the Go runtime behavior, specifically the asmstdcall function and this was how I ended up creating a Windows API tracing tool I named gftrace.

How it works?

The way it works is very straight forward, it injects the gftrace.dll file into a suspended process (the filepath is passed through the command line) and this DLL performs a mid-function hook inside the asmstdcall function. The main thread of the target process is then resumed and the target program starts. At this point, every Windows API call performed by the Go application is analyzed by gftrace and it decides if the obtained information needs to be logged or not based on the filters provided by the user. The tool will only log the functions specified by the user in the gftrace.cfg file.

The tool collects all the API information manipulated by asmstdcall (the c information), formats it and prints to the user. Since the hook is performed after the API call itself gftrace is also able to collect the API function return value.

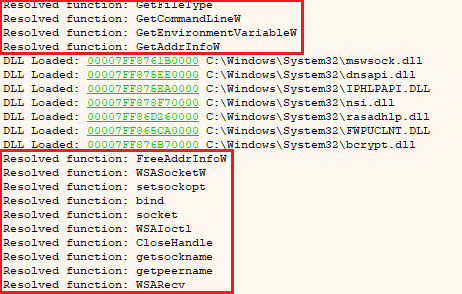

As an example, the following is part of the output generated by the tool against the Sunshuttle malware:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

C:\Users\User>gftrace.exe sunshuttle.exe

- CreateFileW("config.dat.tmp", 0x80000000, 0x3, 0x0, 0x3, 0x1, 0x0) = 0xffffffffffffffff (-1)

- CreateFileW("config.dat.tmp", 0xc0000000, 0x3, 0x0, 0x2, 0x80, 0x0) = 0x198 (408)

- CreateFileW("config.dat.tmp", 0xc0000000, 0x3, 0x0, 0x3, 0x80, 0x0) = 0x1a4 (420)

- WriteFile(0x1a4, 0xc000112780, 0xeb, 0xc0000c79d4, 0x0) = 0x1 (1)

- GetAddrInfoW("reyweb.com", 0x0, 0xc000031f18, 0xc000031e88) = 0x0 (0)

- WSASocketW(0x2, 0x1, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x81) = 0x1f0 (496)

- WSASend(0x1f0, 0xc00004f038, 0x1, 0xc00004f020, 0x0, 0xc00004eff0, 0x0) = 0x0 (0)

- WSARecv(0x1f0, 0xc00004ef60, 0x1, 0xc00004ef48, 0xc00004efd0, 0xc00004ef18, 0x0) = 0xffffffff (-1)

- GetAddrInfoW("reyweb.com", 0x0, 0xc000031f18, 0xc000031e88) = 0x0 (0)

- WSASocketW(0x2, 0x1, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x81) = 0x200 (512)

- WSASend(0x200, 0xc00004f2b8, 0x1, 0xc00004f2a0, 0x0, 0xc00004f270, 0x0) = 0x0 (0)

- WSARecv(0x200, 0xc00004f1e0, 0x1, 0xc00004f1c8, 0xc00004f250, 0xc00004f198, 0x0) = 0xffffffff (-1)

[...]

The simpler the better

Most part of the time in order to monitor API calls you need to hook them in some way and also have a prototype for the function, otherwise would be tricky to guess the number of parameters the function takes as well as the type of those parameters.

gftrace uses the information provided by c to figure what is the name of the function being called and the number of arguments it takes. It also tries to figure the type of the parameters by performing some simple checks to determine if it’s a string, an address, etc. By doing so it does not require any function prototype in order to work and it’s able to trace every single API function performed by a Go application. The only information the user needs to provide in the gftrace.cfg file is a list of the API function names to trace. Simple like that!

Ignoring the runtime noise

During my tests I noticed that one of the last initilization functions called in Golang applications is a init function in the os package. This init function performs a call to syscall_GetCommandLine and that call ends up being a call to the Windows GetCommandLineW function.

What gftrace does is use GetCommandLineW as a kind of sentinel. It waits for this call to happen and only after that it starts to trace the API calls according to the user filters. By doing so it avoids resolving and printing all the API calls performed by the runtime package, making the tool output very clean and focused on the main package calls.

Some other interesting aspects

After spending some time playing with the tool I noticed some interesting things regarding the Windows API calls Go uses:

- It always rely on the unicode version of the Windows functions (CreateFileW, CreateProcessW, GetComputerNameExW, etc).

- Due to the Go design some calls would be very noisy by default before the call to the desired function. As an example, when you execute a command via

cmdin Go it would first perform several calls toCreateFileWbefore a call toCreateProcessW. - Memory and thread management functions such as

VirtualAlloc,GetThreadContext,CreateThread, etc are usually used several times by the runtime and probably will not be used by themainpackage.

I created a config file in gftrace project that considers it all. It does not includes the regular functions used by the runtime and also only filters by the unicode versions. For item 3 it’s up to the user to figure what function is more interesting for each scenario.

Why gftrace might be a good option?

Of course it would always be a matter of preference, there’s some amazing tools available that can handle API tracing, but here’s some reasons I believe gftrace is also a nice option:

- Golang binaries might be a pain to reverse sometimes so this tool can be very handy for fast malware triage for example since it’s very easy and fast to use.

- It performs a single hook in the runtime package without touching any Windows API function and does not require function prototypes. Those things make the tool very portable, fast and reliable.

- It’s designed for Go applications specifically so it handles all the runtime nuances such as the runtime calls noise before the calls from the

mainpackage.

If you want to check how to configure and use the tool make sure you check the project page!

Final thoughts

I need to say I had a lot of fun in this research and eventually I still play with it all. It made me learn A LOT about how Golang Internals work. There’s a few other details I didn’t put here in this blogpost but I might update it in the future.

Regarding the source code, I’ve tried to put as much comments as possible and also make it very clean in order to be easy and nice to people use to study, etc. The tool is still under development and probably has a lot of things to be improved so please threat it as a PoC code for now.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed the reading.

Happy reversing!